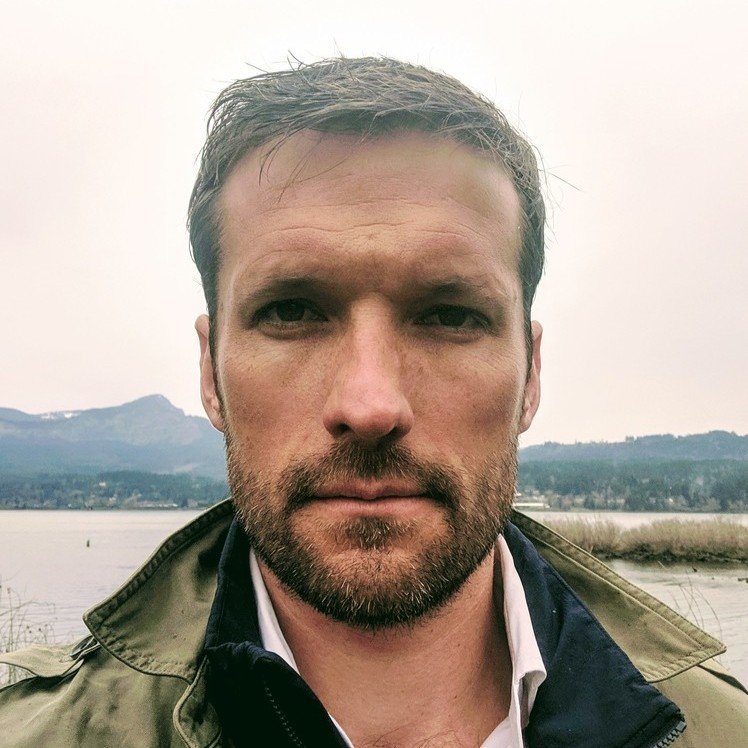

Episode 142: Aaron Ratner, President of Cross River Infrastructure Partners

Today's guest is Aaron Ratner, President of Cross River Infrastructure Partners.

Cross River Infrastructure Partners is a platform of development companies deploying climate technology and capital into sustainable infrastructure projects. It focuses on conversion projects in the climate, renewable energy, and sustainable food spaces.

Aaron has a wide swath of knowledge across finance, investing, and development. He worked in financial services in Hong Kong and commercial impact investing at i2 Capital. Aaron transitioned into sustainable infrastructure investing, taking a developer residency at Generate Capital and as the Managing Director of Ultra Capital. As President at Cross River, Aaron and his team develop and invest in the deployment of climate technologies into sustainable infrastructure projects. In addition, Aaron also serves as a Venture Partner at Vectr Ventures, an early-stage venture studio.

Aaron's perspective and expertise led to a lively discussion about how he got hooked on climate, the infrastructure investment market, and Cross River Infrastructure Partners' role. We also analyze Cleantech 1.0's downfall, the lessons learned, and how Cleantech 2.0 can succeed. Aaron is an exciting guest, and this episode is a must-listen if you are interested in large-scale infrastructure investment and development!

Enjoy the show!

You can find me on Twitter @jjacobs22 or @mcjpod and email at info@myclimatejourney.co, where I encourage you to share your feedback on episodes and suggestions for future topics or guests.

Episode recorded January 25th, 2020.

In Today's episode we cover:

Aaron's climate path and career history

Cross River Infrastructure Partners' mission, role, and model

How infrastructure investing works

Criteria for successful projects and what is missing from those that don't get funding

How a sovereign wealth fund operates and the key differences from an equity fund

Biggest gaps in the capital market today

Cleantech 1.0 and its failures

Differences between how development capital is raised versus project finance capital and where equity capital fits into the equation

How incentive systems have evolved since the early 2000s

The importance of pilot projects to the success of Cleantech 2.0

Areas of infrastructure and development Aaron is most excited by

Aaron's advice for firms investing in infrastructure

Advantages and disadvantages of combining equity capital and project finance under one firm

Motivations for sovereign wealth funds to invest in infrastructure

What sectors of Climatetech Cross River invests in

How Cross River measure impact and success

Barriers holding infrastructure investing back and what the market is lacking

-

Jason Jacobs: Hey everyone, Jason here. Before we get going, I just wanted to take a moment to give a quick shout out to the new paid membership option that we recently rolled out. This option is meant for people that have been getting value from the podcast and want to enable us to keep producing it in a more sustained way.

It's also for people that want extra stuff, such as bonus content, a Slack room that's vibrant and filled with people tackling climate change from a wide range of backgrounds and perspectives, as well as a host of programming and events that get organized in the Slack room. We also have a virtual town hall once a month where you can get a preview of what's to come and provide feedback and input on our direction. We'll be adding more membership benefits over time.

If you wanna learn more, just go to the website, myclimatejourney.co. And if you're already a member, thank you so much for your support. Enjoy the show. Hello everyone. This is Jason Jacobs and welcome to My Climate Journey. This show follows my journey to interview a wide range of guests to better understand and make sense of the formidable problem of climate change and try to figure out how people like you and I can help.

Today's guest is Aaron Ratner, president of Cross River Infrastructure Partners, which is a platform of development companies deploying climate technologies into sustainable infrastructure projects across hydrogen, carbon capture, sustainable agriculture, and renewable energy. Aaron is also a Venture Partner with Vectr Ventures, based in Hong Kong, where he covers climate technologies with a focus on carbon upcycling and hydrogen.

I was excited for this one because climate tech has such a broad definition and coming in with a small high growth venture capital lens is one purview but there’s a whole other wide world as you get into project finance and upcycling and hydrogen and carbon capture and that stuff is some of the highest impact stuff you can do as it relates to decarbonization. So, it’s important to understand.

Aaron has been at it a long time so this episode really gets into the nitty gritty about how this stuff works, where are some of the biggest opportunities are, and what some of the risks are as well. Aaron, welcome to the show.

Aaron Ratner: Thank you for having me.

Jason Jacobs: Excited for you to be here. And it's funny this episode is kind of like a textbook example of the MCJ flywheel working because I first came across you when you joined the MCJ community and I thought your background seemed pretty interesting and then we ended up looking at a handful of investments through the firm that were relevant to the things that you do. And so we reached out to you for some advice and then you had pretty good advice and seemed to know your stuff and it seemed like it'd be a valuable perspective to both someone to learn from and someone to enable the rest of the community to learn from. So we invited you on the show and here we are.

Aaron Ratner: Awesome. Yeah, I'm excited to be here. Thanks again.

Jason Jacobs: So for starters, what is Cross River Infrastructure Partners?

Aaron Ratner: Cross River Infrastructure Partners is a platform of developing companies, deploying climate tech into sustainable infrastructured projects. So we sit in between capital providers who want to be investing in projects and occasionally into startups or technology companies, corporate partners, large corporations who want to be engaging in these kinds of projects and then development teams that are focused on those specific technologies and systems and dedicated to getting those into the project level of the infrastructure world.

Jason Jacobs: Got it. And so when you say sit in the middle of, what role does Cross River play?

Aaron Ratner: Well, we bill ourselves as a platform. So the role we play is we actually set up the development company to work alongside our technology partners. So an example is a technology company in the early stages of commercialization, they're just starting to sell units into the market. Oftentimes in this sector, those companies will benefit from having a no money down solution to offer the market.

And so while they have a sales team trying to sell units or systems, we will work alongside them and deploy whatever they have as a service. So an example would be work we do with a hydrogen production company called BayoTech. They have a containerized unit that can produce up to one ton of hydrogen a day. And their team is out selling units to buyers, we're alongside them deploying 10 year fixed price hydrogen contracts to the customer base that doesn't necessarily want to own the technologies yet because it's in the earlier stages of deployment, but still wants the end product and is interested in moving in that direction.

Jason Jacobs: So is it like a, you guys own the assets and then you lease them to the end customer type of model?

Aaron Ratner: Yeah. So our development company, that one is called Cross Hydrogen, no surprise there, we'll purchase the unit from our technology partner and then deploy it as the developer. So we're actually in the market developing the projects. We're working on sites and inputs and feedstock and off-take contracts. And we are the project manager, so we're the long-term operator of the project.

Jason Jacobs: Cool. And you mentioned that Cross River has a climate tech focus. I'm curious if you look at your history, was it climate that led you into this project and infrastructure world, or was it the project and infrastructure world that led you into climate? How did all that come about?

Aaron Ratner: I ended up where I am today mostly through a very intimate relationship I have with nature, and I think a lot of my partners are the same way. I grew up outside of Boston and-

Jason Jacobs: Did we talk about that? What town did you grow up in?

Aaron Ratner: I grew up in Carlisle, Massachusetts.

Jason Jacobs: Okay.

Aaron Ratner: A small town on the other side of Concord. And so I grew up in Bo-

Jason Jacobs: I grew up in Newton.

Aaron Ratner: I know that.

Jason Jacobs: And I live in Brooklyn now, so we're sort of neighbors, or not too far away from where you grew up at least.

Aaron Ratner: That's right. Yeah. I grew up in a small town. It didn't even have a traffic light when I was a little kid and next to a pretty large forest and spent a lot of time outside in nature and, and always did that growing up in my free time, even as early as high school, I was in the mountains climbing whenever I could be. So I spent a lot of time in nature.

And eventually I went to college and moved to Hong Kong and went in the exact opposite direction and was wearing tailored suits and focusing on money and staying out as late as possible as often as possible. And it, it didn't really serve me very well and I ended up back in the States going to graduate school at Stanford. And several years after that, I joined a woman named Ashley Allen in Washington, DC to help her build a company called i2 Capital Group, which had set out to be an impact investment merchant bank.

Ashley had a very extensive history in impact advisory and we were trying to figure out how to set up a business that would accelerate the deployment of capital into impact investing. And this is almost 10 years ago when people were still trying to figure out what impact investing was. And our first project ended up being a million plus acre mitigation bank in central Wyoming.

So this was a program to acquire 1.3 million acres of land, convert that into permanent conservation land and through that create credits which oil and gas companies would buy to offset their development in Wyoming. It was a very successful project, really exciting and spent a lot of time in Wyoming, which was great. And as I was doing that project, it became very clear to me that the meaning of the work was becoming much more important than the financial upside.

And it was just, even though it was slow going and very difficult, it just felt really great to be doing that with my time and my career. And so I stayed in that for a while and then wanted to get back to the buy-side, the investment side. I met the guys at Generate Capital when they were very early on in putting their company together. I joined them as the first developer and resident at generate.

And so I spent a couple of years with them working on building a sort of a newer natural gas anaerobic digester strategy, which is a lot of fun. We looked at 50 digesters, we acquired two of them. Two of them were both distressed and idled and we turned them around. And then ended up doing a sort of waste to value project in the agriculture sector, after which I left to go focus on projects that were a bit out of the middle of the road for Generate, they were a little bit higher risk and a little bit more cutting edge and just wasn't a good fit for them at the time.

That led me down the path of really being fascinated with the waste of value space, the waste conversion space and what you could do with all of the materials, the organic and inorganic materials that human beings were wasting today, both in energy and physical form. And I worked on a, other projects at Ultra Capital for several years. After several more years of trying to deploy capital through the project finance side, it became clear to me that I really was better suited to be a developer.

And I was interested in trillion dollar markets, carbon capture, hydrogen, things that were really gonna change the world and pure play project level equity finance was a bit of a limitation there. And so I, in continuing on with trying to find ways to deploy as much capital as possible into climate, into sustainable infrastructure, had been working with the guys at Cross River on a few of their projects with Tyson Foods and those started to gain more traction.

So I joined them full-time first as an operating partner and then later in the year became the president of the firm. And today we're focused on four sectors. We're in hydrogen, carbon, sustainable agriculture and renewable energy. And increasingly those verticals are starting to intertwine a little bit, but those are the sectors where we have development companies that are out deploying very specific technologies to try and get early stage commercial projects going in advance of hopefully having very significant pipelines down the road.

Jason Jacobs: You mentioned with Cross River, so it sounds like there are the big companies who have some type of product need. There are the product developers that are bringing these products to bear. There are the capital sources that are funding these projects, and that sounded like you guys sit in the middle and you take on the, is it the things that the developers build that you're then leasing to the big companies or... I'm trying to think the best way to get at this, maybe it would help either with an overview of kind of how this world works or with a specific example that would be illustrative.

Aaron Ratner: The answer's really we have two modalities. One is we co-develop projects. So on occasion we work with development teams that have very specific expertise in a particular vertical, for example, biogas, where they'll come to us. They'll want to be on our platform because we have great sources of capital and capital partners and we have a process for helping projects go from being really great ideas to being very investible from an institutional finance perspective. One of the advantages we have at Cross river is that everybody on the team comes from the buy-side and investment background. So we really understand what it takes to get a project to the finish line, get it funded.

Jason Jacobs: Can I stop you there? So what are the criteria that makes a project a good idea, and then what is missing from those projects that when they fill in, gets unfundable?

Aaron Ratner: So there're sort of six main criteria that we encourage developers to think about and we think about when we contemplate projects. The first is the site, so where is that project gonna be? Are you gonna be able to permit it? The permitting of projects is a potentially binary outcome to the negative.

Jason Jacobs: And the site, so what type of entity would go out and start looking for sites and for what type of solution? Are they solving a particular problem for somebody or are they just gonna build a site because they think it could generate energy, let's say for a number of people if they do it successfully.

Aaron Ratner: Let's take the hydrogen work that we do right now as an example. It all has to be very specific and oriented, otherwise, you just end up spinning your wheels. So in the hydrogen space, we have a partnership with a modular hydrogen production company. So they have a containerized unit that's capable of producing up to one ton of hydrogen on site for customers.

We are the developer of those projects. So we are out in the market prospecting for customers, we're looking for people who want to sign a long-term hydrogen supply contract. Once we find those customers, then we will go in with our engineering partners and find the ideal site, where to locate that particular project. Then you have to study the site, you have to do geotechnical work on the ground, you have to make sure the site's gonna be secure, you have to make sure you're able to cook up to all the utilities.

You're gonna need electricity, natural gas, water. You're going to have to make sure you're gonna be able to get your site permitted and your project permitted. Once you do all that, then you have a pretty good sense of what your project is going to cost. And assuming that the returns are going to be there based on the price you're able to charge for hydrogen, then we turn around to our capital providers and we raise the capital into that development company, into that particular project, at which point we will have signed the long-term hydrogen supply contract.

We will have signed the purchase order for the hydrogen production unit from our technology partner. We will have signed all of the permits and all the site issues. So at that point, it's actually a project at which point we purchase the technology, the equipment, place the order, usually in this sector, it takes anywhere from three to nine months to get delivery of your key equipment and then we go and actually implement.

So we will do the site work, we will install the equipment, we'll commission it and we will take responsibility for operating it over the long-term. Because our returns as a developer, you have sort of two ways you get paid. One is a, you get a small amount of capital when the deal closes, but most of your returns are earned through long-term cash flows. And so that project actually has to work over the next five to 10 years in order for us to make any money on our projects.

Jason Jacobs: And what does the timeframe look like on these projects? And then who is it that is actually paying you, which stakeholder in that equation?

Aaron Ratner: The timeframes on these projects are typically anywhere from 10 to 30 years. If you have a biogas project, you can occasionally sign a very long-term contract to sell the biogas to a corporate buyer. In the case of hydrogen, we're signing 10 year contracts, but they're long-term contracts. These are physical operating projects that are intended to operate for several decades. And the capital comes from a variety of sources.

We work with a handful of sovereign wealth funds, we have some family offices we work with and we have great relationships with all of the sustainable infrastructure funds out there that are raising capital and looking for projects and deals. And so we're always talking to all of our capital sources. And when we bring a development company to the market, we run a process and try to find the best investor for that particular strategy and the capital that is interested in that technology and that sector and hopefully figure out a path to getting the money closed and the projects in the ground as quickly as possible.

Jason Jacobs: It sounds like structurally both from a risk profile and from a returns profile and time horizons and things like that, that it seems pretty different than let's say an equity fund that's focused on the venture capital asset class. So I guess, how is this the same and then how is it different? What expectations, so let's say I was a sovereign wealth fund evaluating, participating in one of these projects with you, what expectations should I have about returns, time horizons, risks, things like that?

Aaron Ratner: Generally in infrastructure investors are looking for, depending on the risk exposure, low to mid-teens returns over the life of the project. And that can be anywhere from 10 to 20 or 30 years. And so it's whether you're a large sovereign wealth fund buying a shipping port or some very big piece of infrastructure, or you're an infrastructure fund buying an anaerobic digester, you're looking for 20, 30 year returns.

If it's solar or something that's been completely de-risked, then you're going to be achieving a single digit return. If you're moving into sectors that are a bit more nascent like bio gas and renewable natural gas, storage, then you can start to see returns that get into the mid-teens. And where Cross River operates is really in the early commercialization.

So we work with technologies and systems that are proven, there's some sort of reference facility out there that's operating but they haven't really hit their stride with starting to sell units in the market. So we're very early to market. We're not so early that we can't point to a unit that's been running and it operates just fine, but we're also there before there are a handful of units that have been operating for a number of years, at which point the investment community would consider it to be de-risked.

So we're there a little bit early, and that requires us to do a little bit more diligence around the preliminary engineering, it requires us to contract with insurance companies, which you can do now. There're some very innovative insurance products out there around early technology deployments. The USDA in fact, is providing very attractive leverage to early technologies to try to support this sector. I'm not sure if I'm answering your question, I don't think I am.

Jason Jacobs: You are. And in terms of the structure. So is someone investing in a fund that has a portfolio of these products or is every project backed individually?

Aaron Ratner: Every of our projects is its own standalone company. It's in fact a business. You're taking a waste stream from a, an operating business, whether that's carbon dioxide or an agriculture residue or something like that, you're converting it as something valuable and selling it on. So and every single project has a CEO of that project and a team of people who wake up every day and are responsible for its outcome.

Now, if you have something very modular that's very equipment oriented, you can have one group of people monitoring several projects. But at a large anaerobic digester or a large organics facility, you need to have a whole team of people who are specifically focused just on that. And then, then a capital in this sector will come in and typically fund a program.

So investors, whether it's the sovereigns or the family offices or the institutions, they're never gonna wanna do just one of them. These projects are quite difficult actually to get closed, particularly when you're at the project equity level. And so the investors typically, if they can do one, they'll want to do as many as possible.

Jason Jacobs: I don't know what the technical term is here, but I'm just trying to get at the percentage of default rates or projects that don't get completed successfully and also what some of the typical causes might be if the project doesn't get to the finish line or generate the returns over the time or horizons that were expected and strived for.

Aaron Ratner: Projects typically don't get to a financial closing where they get funded because the developers don't understand how hard it is to get a project finance. On a typical infrastructure project you have several dozen agreements that need to be signed. It's very different from private equity or venture capital.

A project is designed to be a very steady state operating business. So before you finance it, you need everything papered up and agreed to. And so that requires a tremendous amount of negotiation and work prior to breaking ground, unlike a corporate equity investment where you can make the investment and you know you're going to have a lot of flexibility.

The other sensitivity in project finance and one of the big challenges is that the returns just aren't that high. Because you have to contract everything up, if you're targeting a 15% return over 20 years, you don't really have a lot of room for error. There's not a lot of room before people start to lose their money. In any project that's organic you have very asymmetric risk to the downside meaning because you've contracted everything up, it's very rare, if not impossible, to somehow suddenly make three times the money you thought you would.

So there's the upside is de minimis. But the downside, because it's an actual operating facility, is infinite because every single day there's any number of things that can go wrong. So there's a lot of risk there that needs to be managed and paid attention to by engineering talent before you break ground. The work that needs to get done is significant before you invest.

And so developers who don't understand that often run out of development capital or energy, or the project counterparties just lose interest in the project before it gets financed. So it's very hard to get these projects done, and that's something that really we're trying to change and a lot of other investors are trying to change by trying to figure out ways to make it more formulaic to get projects in the ground.

Because if the climate technology sector is going to succeed, if we are going to have thousands of anaerobic digesters and thousands of waste conversion facilities and carbon capture plans and carbon upcycling facilities, we're going to need a better way to systematically get capital into the project, the project level rather than just into the corporate level.

Jason Jacobs: In terms of the costs before the project gets financed, is that where equity capital comes in in these entities or is that dealt or funded a different way?

Aaron Ratner: That's funded a very different way. That's one of the other gaps in the market today. So the projects are typically funded with equity. And then if there's debt, it's either muni bond debt, which is very cheap capital that you can raise these days, or it's USDA backed up where the USDA is coming in and trying to be very supportive to new economies in agriculture oriented projects and whatnot.

Development capital is probably one of the biggest gaps in the market today. So the project development capital is very expensive and very hard to raise because projects are hard to develop as you've said. And so when you're a developer and you've got an idea, so let's say, you know somebody who's got a 10,000 head dairy who wants to have a renewable natural gas project there, the amount of work that needs to get done before that project is ready to even be evaluated by an institutional investor will cost several hundred thousand dollars.

You have to test the manure to figure out exactly what's going to be in it year round. You have to do some legal work around what are the permits that are going to be required. You have to understand where you're going to put the gas. So in O&G project, you need to create the gas, but then you need to connect it to a pipeline, that's called the interconnect.

And depending on where your project is, if you have to go across multiple geographies, you have to go through someone's backyard, they're going to charge you some money. If you work in a territory where the utilities are difficult to work with, they could charge you a million dollars to connect to their pipeline or put you through a 12 month permitting process. So before a developer is even ready to have a project evaluated by investors, there's six to 12 months and call it a quarter million to half a million dollars that needs to be spent in order to do it right.

And very few developers have that money personally to go and just do on a whim. And because the development company itself doesn't typically own any intellectual property, there's also not a whole lot of value in people investing in a development company like you would in a startup, a technology startup. So the development capital mechanism, now there are a few development capital funds out there.

They're doing a good job of trying to get money deployed, but it's risky and it's expensive. Typically, a development capital investor will put up half a million to a million dollars and double their money at financial closing, plus when that project gets funded, plus earn a piece of the developer's cashflow share. So it's expensive money for developers to take in because the developer often has to pay for the development capital investor's upside.

So the incoming project investor will turn around and say, "Well, that's fine, you raise that money for development, but that's c, should come out of your pocket, not ours." So the market hasn't quite figured out how to create a development capital mechanism that's affordable for developers but also has returns that make it worth it for investors to put more money into it.

And I think that what's coming is more engineering talent is getting involved in development. So there are engineering services firms out there that are deploying the development capital themselves. And those are the folks who know exactly how to do the engineering work to get the project priced right, to get all the permits lined up.

Those are the people that ought to be spending that development money and they're able to understand the risks a little bit better before closing. Our sense is that there are more and more of those kinds of investors coming to the table. But that will be what closes the gap is having an availability of development capital that's willing to take a little bit more risk but puts more potential projects out to market.

Jason Jacobs: So the sovereign wealth funds that you mentioned are investing in more project finance, it sounds like. And then is there a separate set of firms that focus specifically on development capital?

Aaron Ratner: There are, yeah. There are a couple of funds out there that do just development capital. Some of the lenders out there are starting to invest development capital. So they'll show up and they'll give you a million dollars to develop your project, but they take the rights to be the lender. So you have to go and get your project done and then raise the equity. And that's just a return on capital and time. They figure that if they have good developers out there, they should accelerate them towards getting projects done because the return will make it worth it if it's a big enough project.

Jason Jacobs: We're starting to kind of put front and center something that I've been tied up in knots about that I would love to work through live here on the air. It might not be exciting to listen to because maybe they find it boring, but I am, I'm ready. So from what I can gather, in the clean tech wave of the 2000 whatever, threes and fours and fives and eights, and what I've heard anecdotally, is that equity capital tried to do too much where it should have been product finance or maybe development capital.

And what I'm hearing now is that the kinds of projects that you're talking about are a mix of project finance and development capital. I'm not hearing that there's an equity component, but I still hear that there are projects where it does make sense to have equity capital such as venture capital and project finance as part of the same company or involved in the same company and pursuit. So first of all, is what I s, is there anything I said that is factually incorrect? And then as a follow-up to that, when is the scenario where those two worlds intersect in a way that does make sense?

Aaron Ratner: Let's dissect that a little bit. So cleantech 1.0 was generally regarded as an abysmal failure on the venture side. Obviously solar kept progressing storage work, wind, and hydro are now taking off. Cleantech 1.0 was largely driven by venture capitalists who were trying to scale businesses faster than was possible. Infrastructure is a get rich slowly business, it takes time.

And everything you do to accelerate that process creates risk, including moving through iterations of engineering without properly testing the results. And so in cleantech 1.0, you had a lot of people who had a lot of experience in software trying to get into physical infrastructure, and there's just a big difference.

In software, you can iterate as fast as electricity will move through semiconductors, in physical infrastructure, depending on what the project is, if you're in agriculture, for example, you may need the planet to rotate around the sun before you know exactly how it works. So there's just a longer cycle.

Today, there are a couple of things that are different. One is that software is much better than it was 10 years ago. So the work that you could do on engineering and designing these projects is much better. The cost of electricity is a lot lower than it used to be, so the cost of running these projects is significantly less. I think the third big factor is that a lot of big corporations today are becoming increasingly willing to engage in pilot projects.

So it used to be that you had a really good idea, you had to build your first small commercial unit using corporate equity, prove that it worked and then you'd go out and try to convince companies to let you bolt onto their facility or do something with them. One of the things that we're doing at Cross River is we're working with a handful of large established companies that are focused on climate, committed to the outcome and are willing to host pilot projects that are small, insignificant to them, but they'll do it because they realize that if the pilot project works, there are 20 or 50 or a hundred more on the back end of it.

So the incentive systems are changed, the support mechanisms are changed from the corporate side and just the cost of getting your projects done. The, the quality of what you can build today with $5 million versus 10 years ago is dramatically different. So from a corporate equities perspective, you have to raise less capital to get your pilots done than you used to and to have a better sense of what your commercial scale projects are going to need to look like.

Now, that being said, we still have the same situation where if we're going to change the world and we're going to really have an impact on the climate, we're going to need thousands and millions of these projects deployed. And there is no way to do that, funding it just through the corporate level.

There's only so much equity in a startup as it grows that can be sold to raise capital to build projects. And quite frankly, from a cost of capital perspective, it doesn't make any sense to be raising money by selling corporate equity to go and buy land or cement or steel or build a physical operating facility. So this is all going to go better the more we're able to push capital down to the project level.

Jason Jacobs: So your phone rings, I mean, unless you're me and you don't answer your phone in this day and age, but assume you answer your phone, ring, ring, ring and it's someone from Sequoia, someone from Kleiner Perkins, someone from one of these venture capital firms who is concerned about the climate problem, thinks the world is going to be heading in this direction because we needed to in order to survive and preserve different lifeforms and species and ecosystems and food supplies and things like that.

And also just like from a US standpoint, we don't build big stuff anymore and venture capital's supposed to be about working on the most impactful innovations and enough of building the stupid stuff. We're going to like build the real, solve the fundamental problem, so we're coming back. And they ask you, "Hey, you've been doing this infrastructure stuff for so long. What's the stuff that we should look at where firms like you guys are involved and the Generates and the Ultras and all that," and which are the ones that we should run for the hills?

Aaron Ratner: If I knew that I would probably go be a venture capitalist. I think that's probably an easier job than trying to build infrastructure. But one of the challenges is that in the hardware side, the technology side, in most cases, it's a race to the bottom on pricing. Everybody's trying to make the cheapest unit possible so they can sell it into the market. That's what happened with solar, that's what's happening with wind, with storage.

So if you look at hydrogen production, right now there are companies that are reforming hydrogen using natural gas. There are dozens of companies that are trying to create green hydrogen, and they're trying to do it in smaller and smaller scale because hydrogen doesn't travel very quickly. So investing in one of those companies purely at the corporate level entails a lot of risk. But if you can couple it with project deployment, then what you're doing is you're actually creating system sales and you're creating longterm cash flows to the technology company.

So there's a way to sort of do both I think that is a little bit de-risked than just being on the venture capital side. So I think there's a lot of sectors where there's a tremendous amount of risk. But one of the verticals where we see a lot of opportunity is in carbon upcycling. So historically, large carbon dioxide flows that were being captured were sequestered.

And that still is the way it is today, where you've got, if you're bolting onto a large natural gas fired power plant, for example, and capturing the carbon oxide, you have to put it in the ground, it's called enhanced oil recovery, or just sequestration, right? Millions of tons a year. But there's an incredible amount of innovation going on in what we call carbon upcycling, which is taking that CO2 and turning it into some form of product, whether it's algae or plastics or construction materials or diamonds.

And that's a sector where technology innovation is going to have a lot of IP and is going to probably end up being quite profitable because the issue of carbon dioxide emissions is one that's very distributed. It's not going to be possible to capture all the CO2 we need to capture using direct air capture and open air facilities because the off-take markets and the ability to sequester it just isn't going to be correlated to the location of those projects all the time.

Jason Jacobs: So you mentioned a way to diversify some of that risk is through combining the equity capital and the project finance under the roof of one firm. What's confusing to me is that aren't those two different skill sets and different risk and return profiles and different pools of capital that are required? And if so, how does having them under one roof make it any less risky than having two distinct firms that are providing them?

Aaron Ratner: So that's a good point. They are different skillsets. And in fact, also historically, if you are a project finance firm and you take any ownership in the technology company, you preclude yourself from working with all the other competing technologies. And that's, that's sort of an FMO to how a lot of project finance firms work.

For example, to generate capital they'll work with anybody in the storage, for example, because they're trying to get as many storage projects done as they can. So, yeah, that's right. It causes a couple of issues if you do both. But at the same time when you are funding just a project, particularly in the early stages. So when you're in that early commercial deployment where just maybe there's one project that's been done, or maybe a few, or maybe none, you learn a lot in those first few projects.

The projects cost more than they should, they take longer, you get a lot more speed bumps. But if you don't own any corporate equity, if all you own is that project, you create a tremendous amount of value for the startup without capturing any of the upside. There's a case to be made for doing both if you are committed to a particular sector because it allows you to deploy a little bit of capital into the technology company, a lot of capital at the project level and capture all of the benefit from all the lessons learned that you go through in actually getting the projects executed.

Jason Jacobs: Is there any scenario where pure equity capital makes sense?

Aaron Ratner: At the corporate level?

Jason Jacobs: Yeah.

Aaron Ratner: Yeah, absolutely. If you have a technology where there's no longterm contractible cashflow, then you're going to need to fund it with pure corporate equity. So one of the fundamental tenants of project finance is long-term contracted cash flow. Whatever you're taking in, whatever you're selling needs to be under a PPA, if it's solar or energy or in case of our hydrogen company, you've got a 10-year hydrogen off-take contract. You have to have contracted cash flows to de-risk the project to keep the cost of capital down, to make it possible to finance the project. It's sort of this virtual cycle.

In a situation where you don't have any contractable revenue because the market is so early, people don't even really understand how to buy it, or if you're operating in a sector where the large corporate buyers just buy that product annually and that's it, and there's no way to get them to sign a long-term contract, then yeah, you're going to need to finance your project in a scenario which is called merchant, which means you're going to need to do it with corporate equity because the risks are just too high to have anybody come in at the project level and finance it for you.

Jason Jacobs: And you talked about how impact is, what drives you to do the work you do. And it, it also sounds like, I mean, this work is hard and long and risky and capital-intensive and things like that, does the capital that funds this need to be concessionary capital, or what are the motivations of the sovereign wealth funds or other entities that fund this type of work?

Aaron Ratner: It has to start with profitability. Infrastructure investors, and there are great investors out there, need to know how to underwrite a project because that's a value add to developers. It's a value add to Cross River to work with really experienced investors who know how to think about these projects and set them up the right way to give them the highest probability of success.

So it does need to start with the intention to make that project economically sustainable on its own, because if it's not, it's not going to last and it's not going to have an impact, it's just going to have an intention. So it needs to begin with that. But the patience, the volatility, the cycles that you go through in learning how to get these projects done, that requires an intention to address climate change and to deploy capital into the sector and to be part of something that's just starting.

We're actually somewhat in the early days of this movement. It feels like it's been around a while for people who are in the sector, but it's very early days. There are major pools of capital coming into the sector. The biggest energy companies in the world are starting to be the renewable energy companies. All the big technology companies on the planet are trying to go zero carbon emission, carbon negative since their inception. So it's early and there will be a lot of patience required to get to the point where this ecosystem is functioning as efficiently as it, it can be.

Jason Jacobs: And the word climate tech gets thrown around so much, but it's so all encompassing. It could mean consumer software, it could mean enterprise SaaS, it could mean these types of hydrogen project or waste to value or upcycling or things like that. When you say this sector and you just gave the answers that you gave around the types of capital that would be inclined to invest in the category, what is the sector that you're describing? Just to make sure everyone's clear on language.

Aaron Ratner: Through the lens that we operate at Cross River, it's really physical projects. So we don't work in the software space. There's a tremendous amount of interesting work being done in climate software. And that's going to drive a lot of efficiencies, whether it's physical grid efficiency, or supply chain efficiency, decision making systems, all of that needs to be driven by software. And that's very valuable.

That's not really where we are, that's not much of a project finance opportunity. When we think about real scale, how to get billions and eventually trillions of dollars deployed in carbon capture and hydrogen and agriculture waste upcycling and water efficiencies and things like that, then that has to be at the project level. So it's, it's physical projects that are operating over multiple generations.

Jason Jacobs: Since impact is important to you in the work that you do, how do you measure and how do you know if you and if the fund, and if these different projects are on track?

Aaron Ratner: The number one metric is projects in the ground. There's no substitute for breaking ground and building something. And that's probably one of the most satisfying parts of this job, is you actually get to participate in the construction of a physical asset. So much of our lives these days occurs in our minds, all of our relationships, COVID notwithstanding, all of our understanding of who we are exists in our imagination. And to sort of spend your time building of physical projects, really fulfilling. I forget what the question was. What was the question?

Jason Jacobs: The question is I understand that it's fulfilling to bring these physical projects to market, but how do you know that you're making our carbon problem better?

Aaron Ratner: The number one metric really is projects in the ground. And then the core metrics are whether that project is economically sustainable, can it survive on its own without any sort of third-party support? And a lot of what we do, we do measure carbon em, emission reduction. So we recently closed a first of what will be many projects with Tyson Foods, helping to upgrade their wastewater lagoons to renewable natural gas. And there it's a very easy metric.

Previously, they were flaring gas or letting methane seep into the atmosphere and now they're capturing all that gas and converting it to renewable natural gas. That's just a metric that's pretty easy to measure. In most of the sectors in which we operate, there are carbon reduction numbers or reduction in electricity intensity that are easy to quantify.

Jason Jacobs: And when you look at some of the barriers that are maybe holding back the category or changes that could be made from anywhere that could help the category in the aggregate to accelerate faster, what are some of the highest impact things that you would change and what changes would you bring about?

Aaron Ratner: That's a great question. So we see a couple of things happening that we're really encouraged by. One is there's more patient venture capital money coming into the sector. So early stage capital investing in these startups, people with expertise in helping startups ramp up quickly, which is a specific skillset.

Investing through funds that have 10 to 12 year life cycles. So they can be in a company for eight years, not three or four years. And that dealt a significant for the infrastructure space. So more venture capital money and suddenly more patient venture capital money is really important, and we see that. We have more venture firms that we're working with right now, looking at their portfolios and trying to think about where we can push capital down to the projects and help them accelerate.

The other trends we see are really on the corporate partnerships. So five years ago, if you walked into a big corporate and you started talking about sustainability, they would roll their eyes and think of you as a cost center, because it meant you wanted to charge them something or one of them to pay you for something. Today, if you're in front of a big global company and you're talking about sustainability, you're talking to the CFO because you figured out a way to help them save money.

So you're converting their waste streams into something valuable, you're helping them reduce their costs. So in addition to their ability to message their investors that they're taking direct actions on climate, you're actually a profitable part of their business. And that's really a big sea change that's happened in the last couple of years and something that's secular, not cyclical. That's not going to go away. It's just going to become increasingly profitable to be implementing climate projects in every business.

Jason Jacobs: And if one were to look at this like a marketplace where you've got the buyers on one side and you've got the project developers on the other, I guess it's a three-sided marketplace, where are we short, if anywhere?

Aaron Ratner: I think right now there's a shortage and it's changing, but there's a shortage of really great developers out there. There are a lot of developers who mean well and they're trying their best and they're getting their projects done. But so far, a lot of the talent in this sector has gone either to the direct engineering side or the investment side.

And eventually, hopefully, this sector will have more and more early technology companies that have development capabilities or just individuals coming into the sector to be developers of projects who understand how hard it is and understand how to get these projects financed. I think that will catalyze a lot of capital coming into the sector.

The biggest problem we're having right now is that there are, are a lot of projects out there that aren't going very well. Some of the largest, most high-profile waste to value projects in the country are 100% over budget and two years behind schedule. And that's not good for anybody. That dissuades a lot of investors from coming into the sector, it dissuades entrepreneurs from coming in this sector.

But the tide is changing and there are a lot of really smart young people coming into this sector who know they can get it done, they've got the energy, they've got a little bit of naïveté, which always helps when you're young. But as that demographic fills in and people move away from consumer oriented software, things that are just media oriented and trying to really move into climate, we think that there's going to be a lot more talent out there to get these projects done and that will be a big boom to this sector.

Jason Jacobs: So the firms that aren't up to standard, are there common ways that they missed the mark or what is it that the firms that are doing the best work have that the rest of the pack is lacking?

Aaron Ratner: On the development side there, until you have actually completed a project and seen one cross the finish line and seen all the things that need to get done before you get a project financed, it's hard to believe it's that difficult. And just like in any big private equity deal, there's a lot of concessions that need to be made and a lot of compromises and a lot of hard work needs to get done to really finish the job.

So the teams out there that are getting it done have done it before. And so the question is, well, how do you start doing it if you've never done it before? I think there's some of the mechanisms we talked about, there are more investment funds coming into the sector, so there are more investors who are willing to work with developers who don't have a lot of experience. We're also at Cross River, we're building a platform.

So we realized that we enjoy building development companies and we also enjoy working with developers and we're trying to create this ecosystem where we have a lot of support and mechanisms in place so that people can come to us if they have a development strategy, come onto our platform and we can kind of enable them to focus on what they do best and take a lot of the administrative and processing parts of that process off of their hands just as you would a young entrepreneur who had a great idea for a startup.

You would invest venture capital into their business and let them focus on their vision and not so much the backend of that, which can be tedious and time consuming. And in particularly in the project world, you have to get all of that work right or your project will never break ground.

Jason Jacobs: And how important is the policy landscape to your success? And are there any key policy initiatives that would be fundamentally important to be enacted that are not in place today?

Aaron Ratner: We generally steer away from sectors that are very heavily influenced by policy. Where we operate now, we're trying to finance projects that don't need any sort of government support. That being said, we are very active in carbon capture. And so the 45Q, the regulation around pricing carbon capture for either sequestration or enhanced oil recovery is quite cumbersome and is going to need to evolve quite a bit before it's as effective as it is intended.

Right now it's not even a cash credit, which means that if you go and build a $500 million carbon capture project, you get your benefit, your credits come in the form of a tax write-off. So effectively you have to find somebody to invest in your project who has $500 million of taxable income who wants the tax benefits.

There's no actual cash payment for those credits. And so you minimize the investor universe significantly through that regulation. Now, if they change that and they start to create a cash pay for carbon credits, that's going to open up that sector much wider to a much broader investor base, which is going to mean a lot more projects get done.

Jason Jacobs: Great. And in terms of the future, if you had a crystal ball, where do you think you'll be, where do you hope you'll be as a firm if you look out two years, three years, five years, 10 years in the future?

Aaron Ratner: I hope that we're doing exactly what we're doing now but at a much larger scale. Well, we got a great team and we have a lot of young people working with us right now. We have seven interns working with us from Wharton, Duke, we've got some folks from out West as well. I'm hopeful that we can continue to build the team and recruit really high quality, young talent.

I think that the vision that we have of being a platform is something that's going to become increasingly irrelevant as there's more capital coming into this space and more opportunity, but still a dearth of experienced developers in the sector. And so if we can become something akin to like a Y Combinator or some sort of accelerator program where we can help young development teams acquire the skill sets to get their first project done a little bit faster and a little bit cheaper than it would've otherwise taken them, that will start to compound and that will accelerate the deployment of projects.

And that, as we mentioned on this conversation, the ultimate metric is projects in the ground. That's the objective here, is to actually build all this infrastructure in a way where it works on its own and it functions as it's supposed to. Because without that, all of this ends up being just intention and not actually outcome.

Jason Jacobs: And is there anything I didn't ask you that I should have, or any parting words for listeners?

Aaron Ratner: One of the things that we're working on, we're spending a lot of time on at Cross River is connecting the startup world of carbon upcycling to early pilot projects. And we're always looking for young companies that have something that's proven, that's ready for a pilot scale facility where we can help facilitate a corporate relationship and try to get those projects in.

So I think over time, one of the things we're trying to do is really position ourselves as a launch pad for technologies that are proven enough to operate at a small scale and are ready to be financed, but certainly not fully commercial. That's a space where we think there's not a lot of competition at the moment, but there's a tremendous amount of opportunity.

As far as younger listeners, I would encourage everybody if they have the time to read The Infinite Game by Simon Sinek. This sector, climate change, this is not a short term trend. This is actually a very long-term, secular trend for our planet and our species. And it's going to take a lot of time to see success. It's not going to be like the internet sector where you have billionaires popping up after a few years of starting their companies.

And those people in software and the internet sector are very smart and they've done a great job, but in the climate space, it's going to take a little bit longer and it's going to be a little bit harder and just gonna require patience. And so hopefully younger people are calibrating themselves for the mission and allowing themselves a little bit more time to achieve whatever successes they have in their mind that they'll consider to be successes.

Jason Jacobs: That's a great point to end on Aaron. But I really can't thank you enough for coming on the show and being so generous with your time. And I certainly learned a lot, and I think that's a pretty good indicator typically that the listeners will as well. So thank you again and best of luck to you and to the whole Cross River team.

Aaron Ratner: Thank you so much. It's been awesome being part of the My Climate Journey ecosystem. The amount of people in there who are active and interactive and reaching out and communicating is just really inspirational. So it's been a pleasure being part of that and trying to contribute to that and hopefully over time we'll have more opportunity to do so.

Jason Jacobs: Hey everyone, Jason here. Thanks again for joining me on My Climate Journey. If you'd like to learn more about the journey, you can visit us at myclimatejourney.co. Note that is .co not .com. Someday, we'll get the .com, but right now, .co. You can also find me on Twitter at Jjacobs22, where I would encourage you to share your feedback on the episode or suggestions for future guests you'd like to hear. And before I let you go, if you enjoyed the show, please share an episode with a friend or consider leaving a review on iTunes. The lawyers may be say that. Thank you.